Tears in the eyes, bullets on the ground, and blood on the pavements - as injustice prevails. That is Port Said.

The city has witnessed unrest again in March in response to an Egyptian court ruling that sentenced twenty-one Port Said residents to death for alleged involvement in killings that happened during a 1 February 2012 football riot, which left seventy-four dead . More than forty-six were killed in Port Said over the past two months during clashes.

[Riot police throw rocks at protesters from the rooftop of Port Said`s Security Directorate. 7 March 2013

(Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

[Skirmishes between residents and riot police.7 March 2013 (Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

[A police conscript fires a tear gas canister at protesters. 7 March 2013 (Photo by AFP/Jonathan Rashad)]

[A protester throws a tear gas canister back at police during street battles outside Port Said`s Security

Directorate. On the right, poster of a protester killed in January`s clashes visible. 7 March 2013

(Photo by AFP/Jonathan Rashad)]

[A protester throws a tear gas canister back at police during clashes. 7 March 2013

(Photo by AFP/Jonathan Rashad)]

[A protester throws a home-made petrol bomb at police during clashes. 7 March 2013

(Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

[A protester runs away as a special forces police officer fires tear gas during clashes. 7 March 2013

(Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

[Interior Ministry`s special forces chase protesters with shotguns. 7 March 2013 (Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

[Ossama Riyad, twenty-seven, receiving treatment at Al-Amiri hospital after being shot in the waist

by police with metal pellets during clashes. 8 March 2013 (Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

[Residents march in the streets of Port Said in objection to the killing of protesters. 8 March 2013

(Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

.jpg)

[Army soldiers guard the governorate headquarters amidst clashes between residents and riot police.

7 March 2013 (Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

[A protester takes a break after throwing petrol bombs at riot police during clashes outside

Security Directorate. 7 March 2013 (Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

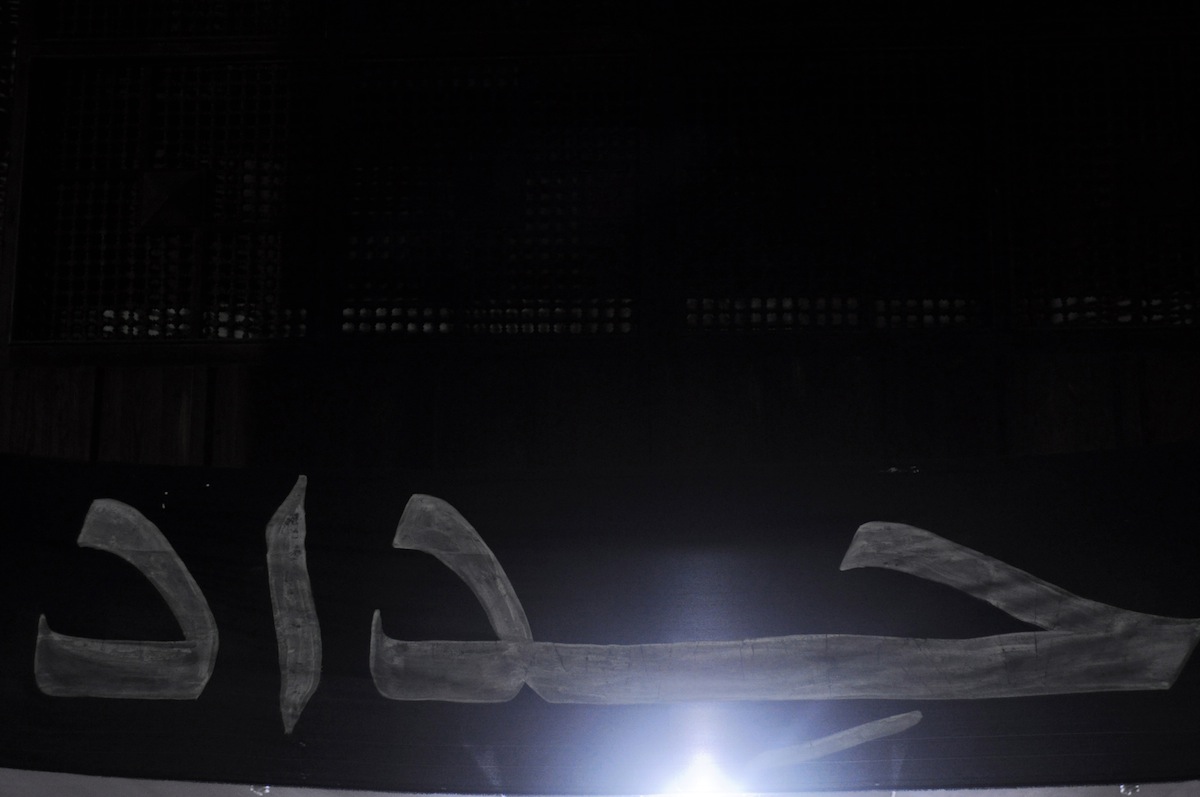

[“Mourning” sign hung outside a school in Port Said. The majority of schools and shops in Port Said

were closed as part of a civil disobedience action, in solidarity with slain protesters. 10 March

2013 (Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

[El-Sharq police station after it was attacked by angry residents. 7.62mm caliber shots can be seen

on the wall. 8 March 2013 (Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

[Lieutenant Mahmoud Nasrallah after getting shot in the face with bird-shot pellets from angry residents.

Nasrallah claimed that three police conscripts were killed during clashes. “Five police officers were taken

hostage by protesters during clashes and were exchanged for protesters we arrested,” adds Lieutenant

Colonel Mohamed Ismail El-Adawy - deputy chief of El-Sharq police station in Port Said. Also, El-Adawy

claimed that police did not use live ammunition. 8 March 2013 (Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

[Funeral march of twenty-four-year-old protester Ahmed Abdelhalim, who was shot in the head during

clashes with police outside Port Said`s Security Directorate. 8 March 2013 (Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

[A protester holds spent bullet casings found after clashes outside Security Directorate. 7 March

2013 (Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

[Military police guard Security Directorate after withdrawal of riot police. Personnel left the headquarters

after Interior Minister gave orders and riot police - along with special forces - went back to the other

governorates - as they were brought from Ismailiya, Arish and Rafah. 8 March 2013

(Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

.jpg)

[Port Said residents gathered by Suez Canal and burned tires to prevent boats from docking, in objection

to the verdict of the football riot trial. As twenty-one were sentenced to death, five sentenced to

twenty-five years, six sentenced to fifteen years, three sentenced to ten years, two sentenced to five

years and twenty-eight acquitted. 9 March 2013 (Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

[Khaled Sedik - a thirty-three-year-old electrician and one of the twenty-eight acquitted - prays

at the grave of protesters killed during recent clashes outside Security Directorate. Sedik was one of those

responsible for security coordination with riot police during the match in February 2012. "We were brutally

tortured and humiliated in prison, they even stopped giving us food and water," he adds. The witness

who testified against Sedik kept changing his testimony, which led to his release. Sedik was jailed for one

year pending investigation. 10 March 2013 (Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

["My life is ruined. My two-year-old daughter keeps saying please God, save Daddy. Kill my husband in a

public square if there`s any concrete evidence that proves he killed anyone," weeps twenty-five-year-

old newly-wed Wafaa Mohamed. Wafaa is the wife of Mohamed Mahmoud El-Boghadady, twenty-six,

a local tuk-tuk driver who was sentenced to death in the stadium riot case. "The coroner said that all

victims were killed due to stampede, so why is my husband charged with “killing intentionally

with a weapon,” asks Wafaa. 10 March 2013 (Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

[Portrait of eighteen-year-old Mohamed Hosni El-Khayat - held by his father - who was sentenced to

twenty-five years in the stadium case. Mr. Hosni claimed that he could not afford to pay a lawyer to help

prove his son`s innocence. "My son was just passing by during the violence around the stadium and

was arrested randomly by police. What`s his charge and where is the evidence that he`s guilty?" Hosni

adds. Worth mentioning: Lieutenant Mahmoud Nasrallah confirmed that many were arrested randomly

following the violence around the stadium area last year. 10 March 2013 (Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

[Mohsen El-Sherif, thirty-three, one of the twenty-one sentenced to death in the stadium massacre, who

is currently a fugitive, as he has not turned himself into police custody. "I had the opportunity to escape

and leave the country many times but I did not because I did not commit a crime. I am innocent.

I was framed by false evidence when I refused to disclose to police the names of members of

Port Said`s Ultras, the Green Eagles," explained Mohsen.

Mohsen was charged with “throwing rocks” and was sentenced in absentia. He claims he is not hiding

and continues his daily life despite facing execution.

"Ahly fans know that the SCAF (the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces) and the Interior Ministry were

behind the massacre. Why do they want to take revenge against the people of Port Said?" added

Mohsen. He said that he would eventually turn himself in. 10 March 2013 (Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]

[A banner that reads "we will never forget you.” The banner includes portraits of protesters killed

during clashes. As more than fort-six have been killed in Port Said over the past two months during

clashes with police. 8 March 2013 (Photo by Jonathan Rashad)]